From Colonial Institute to Royal Tropical Institute and Tropenmuseum

Colonial Museum

In 1871, the Koloniaal Museum, the world’s first colonial museum, opened its doors in Paviljoen Welgelegen in Haarlem, across from Haarlemmerhout park. This museum displayed objects from the Dutch colonies in ‘the East’, primarily from Indonesia, as well as Suriname and the various Caribbean islands in ‘the West’. Centuries of violence, territorial expansion and exploitation had transformed these areas into what were known uncritically at the time as ‘wingewesten’ (exploitable regions), feeding the Dutch national pride. The museum was an initiative of the Nederlandsche Maatschappij tot Bevordering van Nijverheid en Handel (Netherlands Society for the Promotion of Industry and Trade). Slavery had only recently been abolished; in 1860 for Indonesia and 1863 for Suriname and what has been known as the Antilles, and the formerly enslaved would remain under state supervision until 1873. The first contract workers were being recruited from India, then a British colony, to work on plantations in Suriname. The colonial museum emphasized the colonies’ enormous economic potential in raw materials, natural resources and local crafts. The aim was to stimulate the importation of products and to explore their usefulness to Dutch industry, strengthening the Dutch economy through profits from transportation, textiles, foodstuffs, (rattan) furniture, rubber, quinine and much more. The Maatschappij wanted to ‘introduce’ the Dutch population to such products and enterprise. They also wanted to teach visitors about the cultures, religions and practices of people in the colonies who were living under Dutch rule, or who had been sent there as contract workers from other colonial regions. In this way, they hoped to interest young men in a colonial career.

Colonial Institute

In less than half a century, the Koloniaal Museum in Haarlem expanded into an institution of national importance, creating a need for more space. In the fall of 1910, the museum accepted a proposal by several influential Amsterdam citizens in collaboration with the Dutch government, the Ministry of Colonies and the City of Amsterdam. The Koloniaal Museum thus made the move to a larger, more imposing colonial Institute that was to be built in the capital. Similar institutions later arose in various locations throughout Western Europe, such as the Imperial Institute in London, Palais des Colonies in Tervuren, Musée des Colonies in Paris and the Kolonialinstitut in Hamburg. The duties of the Amsterdam Koloniaal Instituut were to promote colonial ‘science’, healthcare, and economic and technological ‘development’.

After the Oosterbegraafplaats (Eastern Cemetery) on Singelgracht at Amsterdam’s eastern edge was cleared and moved to the ‘Nieuwe Ooster’ on 23 October 1915, the construction of the new Institute and the accompanying museum began in January 1916. It combined the collections of the Koloniaal Museum (Colonial Museum) in Haarlem, the Ethnographisch Museum van Artis (Artis Ethnography Museum) and the Vereeniging tot Stichting van een Museum voor Land- en Volkenkunde (Association for the Foundation of a Museum for Geography and Ethnology) in Amsterdam.

Construction of the new institute

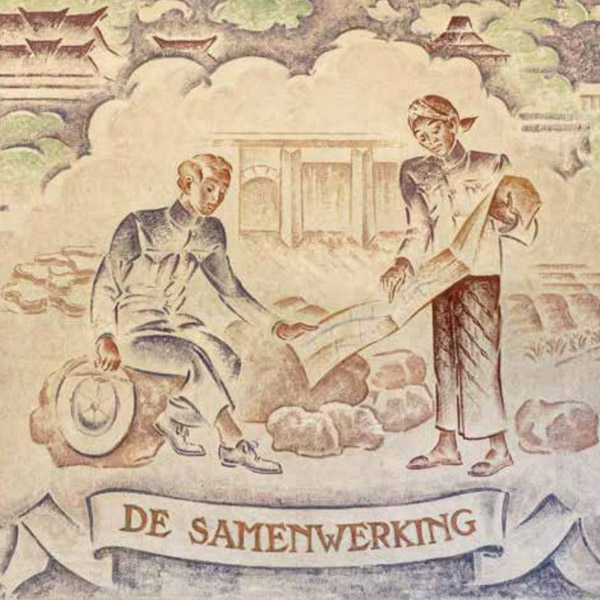

In the early twentieth century, science and museums were closely linked. Scientists from various branches of the social sciences considered Europeans to be the ‘highest level of organised being known to the animal sciences(…)’. They assessed and ranked people and their cultures based on a theory of evolution that conceived human development as a progression through different stages. This prevalent scientific theory was part of the Ethnographic Museum’s mission.

Collection point for knowledge

The Koloniaal Instituut became a collection point for knowledge regarding trade, crafts, agriculture, industry and culture in the colonies. Most of the construction was funded by Dutch companies and private parties with links to the colonial empire. Enterprises with financial interests in the then-Dutch East Indies were most open to the new Institute’s relevance, resulting in a greater focus on the region. In the autumn of 1926, Queen Wilhelmina declared the building officially open.

Departments

The Koloniaal Instituut contained three departments: Trade, Ethnology and Tropical Hygiene. The latter shared a laboratory building with the University of Amsterdam in Oosterpark. It focused on public health in the Netherlands and the colonised territories, and conducted medical research on the prevention and control of diseases. Additionally, the department of Tropical Hygiene explored and developed programs to promote a healthier life in the colonies. Though indigenous medical knowledge was appropriated for the development of medicine, it was barely, if ever, acknowledged.

The other two departments collected objects from the colonies and disseminated knowledge about raw materials, natural resources, the people and their cultures, languages and practices. This was used to train civil servants and company workers destined for the colonies. Each department had its own space within the museum. Educating the public was another important policy objective, which was achieved through the display of objects in the museum and the provision of information packs to Dutch schools. In these ways, the Koloniaal Instituut played an important societal role in spreading colonial thinking and the preservation of the colonial system.

A new name, a new purpose

The Koloniaal Instituut continued its work to a limited extent through the start of the Second World War until it closed in 1944. Part of the building was used to house the German police. As early as the final months of the war, the Board of Directors was already pondering a new name for the Institute. The directors expected that with the 1941 Atlantic Charter and the intended post-war establishment of the United Nations, the term ‘colonial’ would cease to be acceptable. Furthermore, a new name was not enough; the Institute also needed a new purpose. To emphasise the inseparability of the Netherlands, Indonesia and the West Indies, they opted for ‘Indisch Instituut’ (Institute of the Indies). Then in 1945, the Republic of Indonesia unilaterally declared its independence, though it took another four years of negotiations and armed conflict for the Netherlands to accept this in 1949. It was time for another change of course. In 1950, the Institute was renamed Koninklijk Instituut voor de Tropen (Royal Tropical Institute, KIT) and the museum became the Tropenmuseum.

The focus shifted from the colonies to ‘achieving the great task that the Western countries have set themselves with regard to the tropics and promoting the Netherlands’ economic development’. The new Institute and museum would fall under the authority of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, particularly development aid, and concentrated fully on the support and promotion of such projects. This change in circumstances also affected the Tropenmuseum. In the 1960s and 1970s, it organised exhibitions to present and explain ‘all the various facets of development issues to the general public, entirely in line with the development process’s own dynamic character’.

Hotel and training centre

In the following decades, the KIT added a new hotel and a training centre for visiting experts on agriculture and healthcare in the Global South, among other guests. This training involved programs for tropical doctors and so-called technical assistants and volunteers – experts who were to spend shorter or longer periods working on agricultural projects or for government organisations in what was then called the ‘Third World’. A Tropentheater was launched to highlight the works of artistes from these ‘developing countries’. This was followed by a children’s museum. A major renovation in the 1970s provided the museum with a new, ‘low threshold’ entrance, as museum accessibility had become a hot topic, both literally and socially. A new underground collections depot was added in 2000, along with an entirely new training centre on the Linnaeusstraat, behind the former Muiderkerk tower.

Start SDG House

As a consequence of the 2010 economic crisis, and subsequent debate about the use of the national budget for development aid, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs decided in 2014 to stop funding KIT. The theatre and library closed and the library’s heritage collections passed to Leiden University. However, the KIT continued its activities as a knowledge repository for sustainable agriculture, public health and gender in the Global South, and the building entertained around 70 organisations in the field of sustainable entrepreneurship. In 2018, Kofi Annan, then-secretary general of the United Nations, dubbed it ‘SDG House’, a gathering place for sustainable businesses and start-ups that are working towards the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals.

Foundation National Museum of World Cultures

Due to these developments and as part of the KIT, the Tropenmuseum struggled and they formally cut ties with one another in 2014. The museum’s collection is now owned by the national government. The museum itself has merged with Museum Volkenkunde in Leiden and the Afrika Museum in Berg and Dal, to become the Stichting Nationaal Museum van Wereldculturen (foundation National Museum of World Cultures). In 2017, the NMVW entered a structural collaboration with Stichting Wereldmuseum Rotterdam (Worldmuseum).

After almost a century together, working towards the same mission, the Tropenmuseum and KIT are now separate institutions. However, our shared colonial past, memorialised in this building, continues to connect us, as does our shared vision regarding more equitable and sustainable futures.