Tense dialogues

By Mark schneiders and Wayne Modest

The past is all around us. In a sense, this is what we call heritage: that past that remains, that we, as individuals or as a society, find important, to remember, to commemorate, to celebrate. We commemorate victories won and lost, revolutionary struggles and liberations, independence fought for or gained. We remember individuals, or groups of people, whom we believe have played an important role in defining who we are. We celebrate personal or national ingenuity and achievements from the past for which we are proud. And, while the term heritage often holds positive connotations for many, we can also speak of uncomfortable, ‘negative’, even difficult pasts, which we also live with. Often such ‘negative’ pasts, of historical injustice, loss or of victimhood, for example, or our colonial past, are the pasts we prefer to forget.

How to live with the past?

That we live with the past in the present is therefore self-evident. What may be more contentious is how to live with the past, or what to do with what remains of the past in the present. We choose what pasts are remembered or forgotten; this makes the past political. What should national or local governments do with monuments or streets named to honour colonial ‘heroes’? How should the colonial past be taught in schools? How do we name and interpret long-accepted historical periodisation; for example, that commonly called ‘The Golden Age’? Whom do we choose for our historical ‘heroes’, how do we remember the victims of history and who is left out entirely? What should museums like the Tropenmuseum (Museum of the Tropics) do with artefacts collected during the colonial period, including human remains?

Different sides of the same coin

Such questions are receiving increasing attention in current societal debates, and among a broader audience. For some, these debates risk resulting in an increasingly polarised society. For others, it is necessary, a reckoning that is needed if we are to heal the injustices of the past. For us at the Royal Tropical Institute and the Tropenmuseum, these are not mutually exclusive; rather, they might be different sides of the same coin. And it is exactly with these concerns, with this growing politics of the colonial past, in mind that we have produced this guide as a contribution to these discussions.

Example of how the past lives in the present

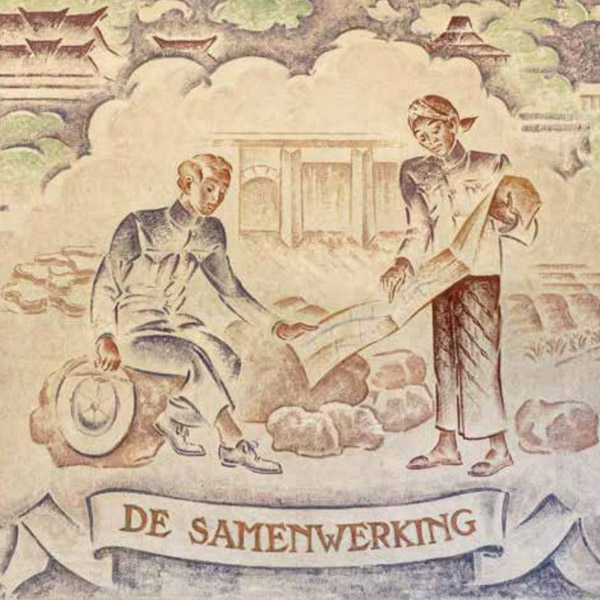

As this guide will show, the building of the Royal Tropical Institute (KIT), which also houses the Tropenmuseum, is an important example of how the past lives in the present. Built in the second decade of the 20th century, the building materialises the ideologies that supported the Dutch, indeed Europe’s, colonial project. It was part of colonialism’s infrastructure.

It is embellished with depictions of ‘encounter’ and exploration, of Europe’s presumed superiority and modernity. It tells of the economic and scientific opportunities of colonised countries and peoples that were to be exploited. And there are stories of the colonised peoples, their rituals and their religions. Etched in stone are stories of grandeur and national pride. This is a conventional reading of the building, as an archive of a ‘glorious’ colonial past. And, in fact, this is the story that most of us have come to know about the building.

Address the injustices of the past

As part of the growing move to complicate such readings of the Dutch colonial history, this guide invites contemporary visitors to read the building against the grain. Some may think that to write a story that is not one of pride would mean a story of guilt. Yet we, as institutions, see this otherwise. Our intention here is not to tell a story that takes guilt as culpability – it would be hard for any of us living today to be culpable for things that happened so long ago. Rather, we see this as part of our responsibility to address the injustices of the past. Such is the approach that this guide takes.

This guide comes at a moment when there are growing demands for the removal of monuments in the public domain, monuments that were intended to celebrate the colonial past. We understand such demands. After all, our relation to the past is always changing and our perception of what constitutes heritage is dynamic. Yet the approach of this guide is somewhat different. Rather than removing the buildings’ decorations to rid it of symbols of the past, we aim to confront the past, to learn from it. But it doesn’t stop there. For us, this guide is a dialogue with the past, albeit a tense one, that should help us to contribute to creating better, more equitable, futures. Such is the work of KIT Royal Tropical Institute and the Tropenmuseum, the two institutes that reside in the building.

Critical artistic reflections by Brian Elstak

This dialogue, furthermore, is not simply taking place between our two institutions. Over the years, we have come to admit how hard it is to see things differently from inside the institution. Thus, this is also a dialogue with several collaborators, from outside our institutions, who have helped us to look at ourselves more critically. This includes artist Brian Elstak, whom we invited to give his own artistic reflections on the building. As is his tradition, Elstak’s criticism is frontal yet nuanced, it is serious and rigorous yet light-hearted. His work is not just a dialogue with us as institutions, it is also a dialogue with the building as form and as style. His drawings, in a comic style, push against the grain of the more glorifying symbolism of the building itself. Elstak offers us a different entryway into re-telling our history in the present, another lens through which we can see ourselves.

Use history to create better presents and futures

As institutions that started out together almost a century ago, but which are now separate, what still holds us together is not simply the fact that we are housed in the same building, but also our shared goals for peace and prosperity for people and the planet, now and into the future. With this guide, we invite you to this dialogue with the past, and hope that you will share our vision to use history to create better presents and futures.

Mark Schneiders and Wayne Modest