ARCHICTECTURE AND ORMANENTATION OF A ‘REMARKABLE BUILDING’

Around 1910, the Vereeniging Koloniaal Instituut engaged the Van Nieukerken family of architects to handle the design and construction of its new building. The Van Nieukerken father and sons named the project De Behouden Reis (safe journey). They drew inspiration from Dutch historical examples, particularly castles in the Dutch Renaissance style of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. This is visible in the multicoloured stone (stairwell) facades, the ornamentation and the use of buttresses and stylised anchor plates.

Art and craft

The historicising style and decorative detailing were purposeful; the Van Nieukerkens believed that architecture should combine both art and craft. The style was seen as characteristically Dutch and commemorated the nation’s ‘glory days’. The architects collaborated with artists from their own network, such as Louis Vreugde (1868-1936) for the sculptures and Willem Retera (1858-1930) for the relief carvings, which were partially based on drawings by W.O.J. (Wijnand) Nieuwenkamp (1874-1950).

Committee for Symbolism

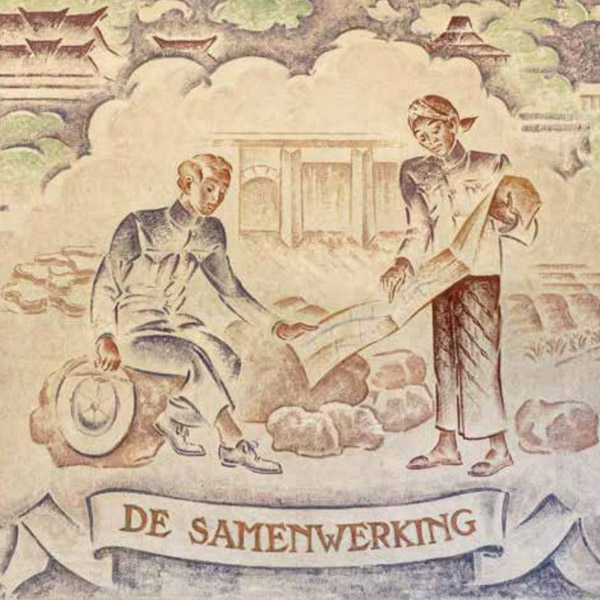

They made use of modern materials such as concrete, and the design included a modern electrical system and alarm installation. The design was criticised by other architects, who considered the lavish, ornate style overly traditional, old-fashioned and expensive. They also thought the design lacked balance and unity and didn’t fit its surroundings. A Committee for Symbolism ensured that the sculptures and paintings expressed the Institute’s mission. There are over 200 decorative elements altogether. The committee also requested what was believed to be an archetypically Dutch artisanal interior, with brickwork, mullioned windows, reception rooms with plush wall coverings and ceramic tiles from the best workshops. As the Institute was scientific in purpose, embellishments were to be sober. The grandeur lay in the choice of materials, such as the various marbles in the ‘Marble Hall’.

To raise funds, committee members approached private citizens and businesses in the Netherlands and ‘the East’. In addition to entrepreneurs and politicians, often with ties to the colonial enterprise, the architects, artists, directors and committee members also made financial contributions.

Stimulate awareness

The building features many more decorative elements than the fourteen described here in this guide. The ornaments symbolise the Institute’s founding and areas of activity, events from colonial history between the seventeenth and early twentieth centuries, and (social-cultural) life in the Indonesian archipelago. In spite of the intended soberness, the building is embellished throughout, from the door handles to the toilets. Everywhere you look are depictions of plants, flowers, animals, religions, agriculture, crafts and historic events with colonial connotations. People regarded by some as ‘heroes’ of the VOC (Dutch East India Company, officially United East India Company), colonial civil servants and the Institute’s founders feature visibly throughout the building. The glorification of such people and the Dutch nation state, like their depictions on the building, is becoming increasingly less self-evident and more controversial. To stimulate awareness of the changing approaches to our past, we will discuss several decorative elements in more detail.